Meditating in Madison Square Park, Manhattan, New York City (Wikipedia)

Often people use the terms visualisation, meditation and pathworking interchangeably, but they are different techniques, with different purposes and histories of development.

A meditation invites you to focus on your breathing, your body, or your feelings; it does not usually involve visualising. It is designed to increase awareness of your body. Typically, meditation techniques are drawn from Taoism or Buddhism.

Another related technique is contemplation, where the practitioner focuses on a deity, virtue, or quality (such as love). The technique is used in both Christianity and Islam, but was also advocated by Plato. Examples of contemplation include contemplative prayer, centering prayer, and lectio divina. Some people contemplate Nature as a spiritual practice.

A visualisation invites you to focus on specific images; sometimes it tells a story or involves travelling through a landscape (real or imaginary); sometimes it is intended to bring about a specific result – this is known as creative visualisation. Visualisation is popular with both Pagans and New Agers.

A pathworking takes you on a journey through an inner landscape. Pathworking as a technique is derived from magical uses of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. In that system, a pathworking is a journey along one of the 22 paths of the Tree of Life, each of which has a specific set of landscape and symbolism associated with it (and corresponds to one of the twenty-two cards of the Major Arcana of the Tarot).

I would say that guided meditations were suitable for large groups; guided visualisations and pathworkings should probably be used in smaller groups where the person leading can be more aware of participants’ emotional responses.

Some visualisations are not safe (e.g. ones that invite you to visualise going out of your body) and should not be attempted by the inexperienced. People often think that it’s all happening in your head and therefore you can visualise whatever you like with no consequences, but that is not necessarily the case. Magic (defined here as “the art of changing consciousness in accordance with will”) does have real effects, even if they’re only psychological effects.

I never pre-record either visualisations or meditations – I prefer to do them live and feel the mood of the participants, going slower or faster depending on whether I feel the participants are following, and adding bits for the specific audience. Also, I would always try out a visualisation myself before leading others in it.

I have come across a lot of people who cannot visualise at all. For small group work, I always ask if there are people who can’t visualise, and adapt by talking about feelings and spatial cues as well as visual imagery.

You can test whether someone can visualise by getting them to think of an orange – most people can manage to see an orange sphere in their mind’s eye, and if they can’t, the chances are that they are one of those people who cannot see with their mind’s eye. I, and several other people that I know, can taste on my mind’s tongue (and smell on my mind’s nose) but many people can’t do this.

You can check whether people can experience all five senses with the orange visualisation – imagine touching the pitted surface, prising the fruit open with your fingers, hearing the noise of the tearing peel, smelling the orange oil from the skin and the juice inside, then tasting the fruit, and feeling the juice on your tongue. For people who can’t visualise in any sense modality, get them to remember the emotional feeling they get when they eat an orange; you can then use the same approach for other visualisations.

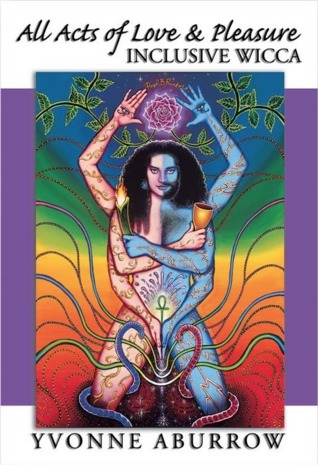

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.