Queer Paganism by Jo Green

I found myself nodding and smiling in agreement throughout most of this book. The author’s sensible and down-to-earth approach to magic and Paganism was very much in tune with my way of thinking. They [1] also have an exceptionally clear style of writing, which makes the book a pleasure to read.

The book’s subtitle is “A spirituality that embraces all identities” and the author has done their best to include everyone in the LGBTQIA+ community and heterosexuals too. This book would definitely be of interest to queer Pagans and open-minded heterosexuals. It is not only about queer Paganism, but is about inclusive practice. It is very Wicca-flavoured though, so if Wicca isn’t your thing, you might not like it.

Exploring Queer Paganism

The first chapter explores the meanings of Queer and Paganism. It explains that Paganism, Wicca, and Witchcraft are distinct but overlapping. The second chapter looks at how the standard binary thinking of many Pagans (male/female, light/dark, etc) doesn’t include those of us who don’t fit neatly into a cisgender and heterosexual view of the world. Each section of the discussion unfolds clearly and neatly from the previous section of the discussion. This could be very helpful for those people who still haven’t understood why many (perhaps most) queer people have an issue with the deification of the “masculine and feminine principles”. The next chapter goes on to explore concepts of deity and energy, and how these fit together in a worldview that is not based on the idea of a “masculine principle” interacting with a “feminine principle”.

Queer Magic

The second part of the book deals with Magic, and includes an excellent chapter on how magic works (again, very similar to my own ideas on the topic). It also looks at how magic and science interact. The section on the Hermetic principles as described in The Kybalion, which explains how they relate to a queer worldview, is outstanding. This is followed by a chapter on ethics, which was excellent on the topic of magical ethics, but would have been better if it explored the Pagan ethics of life in general.

Living as a Pagan

The third section of the book deals with Pagan life, including living as a Pagan, the importance of balance, how to choose a magical name, and relationships with deities. The chapter on the festivals was disappointing, as it was mainly about the view of the Sabbats as the unfolding story of “the Goddess and the God” which I personally find unhelpful from a queer point of view. It does cover the folk customs associated with the festivals though, so you could build out from these to develop something more inclusive. It explains how to adapt the festivals for use in the Southern Hemisphere, which is good. It also mentions that you can choose to celebrate them on the day when the appropriate seasonal vegetation comes into flower, which I liked. I would have liked to see more information on how to adapt the festivals to be more inclusive of other sexualities (but I have covered this in my book, if you’re interested). The chapter on the esbats and the phases of the Moon was helpful, though.

Meditation and Visualisation

The fourth part of the book covers meditation and visualisation. This includes a technique which the author says is helpful for easing body dysphoria. I have seen this meditation before (and it’s the only technique that I find actually helps me to relax) but I didn’t know it was good for dysphoria, so that’s really useful to know. The section on building an astral temple is also excellent, as it points out that an astral temple doesn’t have to be a building, and can be a grove of trees. I had always assumed that it was supposed to be a building of some kind, and had terrible difficulty building one. I do however, have a grove of trees on the astral, and a rather nice stone circle, either of which could be my astral temple. So that section cleared up a longstanding difficulty for me! The chapter on the chakras is very good (and uses the proper Sanskrit names) but draws on the Western idea of the chakras, which is somewhat different from the Buddhist view of them.

Queer Correspondences

The next section explores magical correspondences, including deities, non-binary deities, queer deities, moon phases and the menstrual cycle (but described in an inclusive [2] way), orgasm mysteries, the four elements, days of the week, colours, and magical tools. This provides the basis of a system of magic that is properly queer-inclusive. I particularly liked the section on colour symbolism. This section also explains the difference between widdershins and deosil, and why they are different in the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere.

Queer Ritual

The section on ritual was very helpful, as it goes through how to set up the circle, cleansing the space, calling the quarters, and consecrating the tools and the participants. One caveat on this section though: the author mentions that the high priestess and high priest have absolute authority in the circle (p. 128). I wouldn’t go that far, as they do not have the right to ask you to do something that the vast majority of people would be uncomfortable with, such as French kissing, sex with other people in the circle, or anything massively humiliating. Some of the things that ritual involves may be slightly outside your comfort zone, but that’s why it is a really good idea to have a quick chat beforehand about what is going to happen in the ritual. Other than that, this section is really great and has lots of excellent ideas like having three ritual leaders, one for the God, one for the Goddess, and one for non-binary deity (the Universal, as the author refers to it).

Divination

The final section of the book deals with divination, including gematria (finding the magical number of your name), Tarot, runes, scrying, and palmistry. This section was also very good, especially the section on the magical meaning of numbers.

An excellent addition to your Queer Pagan bookshelf

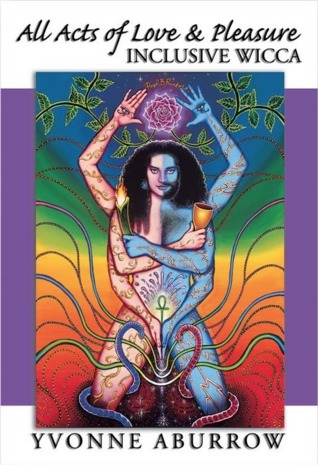

All in all, a very enjoyable read. The book is well-thought-out, and it is very easy to find things again when you want to use it as a how-to guide for magical practice. There were a few typographical errors here and there, but they didn’t detract from my enjoyment or understanding of the book, and they were more than made up for by the exceptionally clear writing style. The author’s lovely drawings also grace the text, and help to explain the magical concepts being discussed.

The book is an excellent contribution to the literature on inclusive and queer Paganism and witchcraft, and I would recommend it to anyone who is interested in making their practice more inclusive and welcoming to LGBTQIA+ Pagans.

Where to get the book:

- Amazon.co.uk – Kindle edition, full-colour paperback, or black-and-white paperback.

- Amazon.com – Kindle edition, full-colour paperback, black-and-white paperback.

- Thrift Books – full-colour paperback, black-and white paperback.

Notes

- The author’s preferred pronoun is they [Back]

- The male brain also has cycles governed by the hypothalamus [Back]

I was not sent this book for review. I bought it myself and reviewed it of my own free will and accord. Please do not send me books for review, as I generally dislike writing book reviews, and only reviewed this book because I thought it was important and worth drawing attention to.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.

![Valencia, Spain. [CC0 Public Domain] Pixabay](https://i0.wp.com/wp.production.patheos.com/blogs/sermonsfromthemound/files/2016/12/valencia-1049389_960_720-300x200.jpg)