Paganism is an umbrella term for a group of religions that venerate the Earth and Nature, and the ancient Pagan deities. These religions include Wicca, Druidry, Heathenry, Religio Romana, Animism, Shamanism, Eclectic Pagans and various other traditions. All of these traditions share an urge to celebrate life and to honour our connection with all other beings on the planet. Pagans often emphasise the cyclical nature of reality, and so enjoy the cycle of the seasons and the dance of Sun and Moon.

Green is the colour everyone immediately associates with Paganism. It is the colour of nature, of trees, and all growing things. It is associated with the Green Man, a symbol of our connection to Nature, and a manifestation of the life-force. Many Pagans also like the colour purple for its spiritual connotations (it is associated with the crown chakra). Interestingly, purple and green were also the colours of the suffragette movement.

Photo by OceanBlue-AU [BY-NC-ND 2.0]

The metals are traditionally associated with the heavenly bodies: gold for the Sun, silver for the Moon and the stars, mercury for Mercury, copper for Venus, iron for Mars, tin for Jupiter and lead for Saturn.

The white, red and and black colours of the Triple Goddess owe a lot to Robert Graves’ seminal work The White Goddess. He derived it from the tendency of the Irish myths to declare those “otherworldly” colours in combination, such as the red-eared white cow that was Brigid’s only food as an infant, the red, white and black oystercatcher that is called “Brigid’s bird” or the red-eared white dogs that occur in so many stories as Otherworld animals.

The four elements are very important in Paganism, and different mythological systems associate them with different colours. Earth is associated with stability, fertility, strength and nurturing, and can be represented by green, brown, or white. Air symbolises intellect, the breath of life, and the spirit, and can be depicted as yellow, white, or black. Fire represents energy, intuition, passion and vitality, and can be orange or red. Water represents love, emotion, fluidity, and healing, and can be blue or green.

The rainbow is an important symbol for Pagans. To Heathens, it the symbol of Bifrost, the rainbow bridge between the world of deities (Asgard) and the world of humans (Midgard). For many Pagans, the colours of the rainbow correspond to the colours of the chakras (borrowed from Hinduism). It is also the symbol of LGBT sexuality.

Photo by Nicholas_T [BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Diana Paxson and her branch of Asatru (a Heathen tradition) associate colours with deities: Oðinn is black and blue; Thor red; Freya and Freyr green and gold, or sometimes brown.

White is the colour of light, and is associated with the Maiden aspect of the Triple Goddess. It is also the colour most often chosen for Druid robes, because of its association with the Sun.

Black is the colour of darkness, but for Pagans, darkness symbolises a time of rest, dreams, and the hidden powers of Nature. It is also a symbol of the fertile earth, in whose dark depths seeds can germinate. It is also the colour of death and the underworld, but death is seen as part of the cycle of life, death and rebirth, and so is not to be feared. For some Pagans, black is the colour of the Crone aspect of the Triple Goddess, and so represents the wisdom of old age. It is also the colour of women, of the cycles of the human body, and of those people considered “non-white.” Black speaks to our love of mystery, night, and the realms of the unconscious and “starlight” consciousness. It’s the color of soil, dirt, compost. It represents wholeness.

Important Pagan Dates

There are different Pagan festivals depending on which Pagan path you follow, but many Pagans celebrate the festivals of the Wiccan and Druid Wheel of the Year.

Samhain or Hallowe’en falls on 31st October, and is a festival of the ancestors and the otherworld. Its colours are autumnal: the orange skin of pumpkins, the rich reds and golds of autumn leaves, and the brown colour of the bare fields. Heathens celebrate the festival of Winternights around this time; historically this was a big sacrificial feast at which gods, elves and/or ancestors were welcomed. Nowadays Heathens make offerings of mead to the deities and wights (powers).

Yule or Winter Solstice is on 21st or 22nd December, when we celebrate the return of the light as the days begin to lengthen again. The colours of Yule are red and green for the holly and its berries, dark green for the evergreens that are brought into the house, the green and white of the mistletoe, gold for the returning Sun. The Romans celebrated Saturnalia at this time, which is where the customs of the Lord of Misrule and giving presents come from, as the masters had to serve their slaves and give them gifts.

Imbolc, celebrated on 2nd February, is when the ewes begin to lactate, and it is associated with the Celtic Goddess Brighid, lady of smithcraft, healing and poetry. The colours of Imbolc are white and red; white for the ewes’ milk and the swan, which is the bird of Brighid, and red for the new growth on the trees, and for the fire of Brighid.

Photo by Juggling Mom [BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Spring Equinox usually falls on 21st or 22nd March, and is often represented as being darkness and light in dynamic balance, because the days and nights are equal – but the light is in the ascendancy. The goddess of this festival is only known from a reference by the Venerable Bede, but it has been suggested that she may have been a goddess of Spring and of the Moon, since hares are sacred to the Moon and are associated with this festival.

The Festival of Beltane falls on 30th April and 1st May, and celebrates life, love and fertility. Its main colour is green – the fresh green of the leaves on the trees. This is the time of year for Maypoles (traditionally decorated with multicoloured ribbons) and for leaping over the Bel-fire with your beloved.

Photo by yksin [BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Summer Solstice usually falls on 21st or 22nd June, and its colours are yellow (for the Sun and for the St John’s Wort flower, which is the flower of Midsummer) and red (for the heat of the Sun).

Lughnasadh or Lammas is the Harvest Festival, and is celebrated on 31st July and 1st August. Its colours are the colours of the harvest: the gold of ripening wheat and the harsh light of the Sun, and sometimes red for the poppies that grow among the corn.

This post was originally published at the Colour Lovers blog on 14 November 2007. It was part of a series on colour symbolism in different religious traditions:

See also: The Colorful Diwali Festival of Light

Acknowledgements and Sources

- M Macha Nightmare – information about green and purple

- Inanna – comments on the colour

- Dana Kramer Rolls – information about Asatru deity colours

- Brenda Daverin – information about the connection of the Triple Goddess colours with Irish myths.

- Chas Clifton – connection of the Triple Goddess colours with Robert Graves

- The Four Classical Elements, Patti Wigington

- Winternights, Stormerne and Arlea Hunt-Anschütz

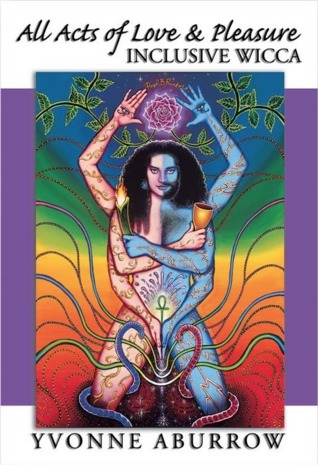

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.