This was an address at Memorial (Unitarian) Church, Cambridge, on 29 May 2016. In it, I explain what Wicca is, situating it in the context of other historical and cultural developments, and then talking about why I love Wicca.

Order of Service

- Chalice lighting: This earthen chalice by Edwin A Lane (UUA)

Opening prayer: From the rising of the Sun (A NeoPlatonist / Taoist / Unitarian version of Psalm 113), by Yvonne Aburrow - 1st hymn (147 Purple book): Spirit of earth, root, stone and tree, Lyanne Mitchell

- Reading: Circle, by Yvonne Aburrow

- Prayer: Mother Spirit, by Yvonne Aburrow

- Story: Where is God, by Anon – Bengali folktale

- 2nd hymn (104 purple book): Name unnamed, by Brian Wren

- Reading: The Charge of the Goddess, by Doreen Valiente (Wiccan)

- Meditation: grounding and centering

- 3rd hymn (207 in UU hymnal): Blue Boat Home, by Peter Mayer

- Address: Why I am a Wiccan

- 4th hymn (164 purple book): The secret pulse of freedom throbs, by Yvonne Aburrow

- Closing blessing: Mothering all the way down, by Andrew Brown

What is Wicca?

Wicca is primarily a religion where the practitioners interact with the world on many levels – physical, spiritual, magical and emotional. Initiatory Wicca is essentially an esoteric mystery religion in which every practitioner is a priestess or priest. A mystery religion is one in which the dramas of the psyche are enacted by and for the benefit of its initiates, but because these mysteries often involve non-verbal concepts, they cannot be communicated.

There are three degrees in initiatory Wicca. After the first degree initiation, the initiate is responsible for their own spiritual development (a priest unto themselves); in some groups, the period between first and second is where the new initiate is helped to develop their spirituality by their Coven and High Priestess and High Priest; after the second, they may take on responsibility for assisting others’ development; after the third, their psyche is fully integrated with itself.

Modern initiatory Wicca has many variants (Gardnerian, Alexandrian, and offshoots of these) but all share an adherence to a similar ritual structure and the practice of initiation.

The contemporary Craft both draws upon its roots in the Western Mystery Tradition, and looks to traditional forms of folk magic, folklore, and the pagan traditions of the British Isles for inspiration. The structure of rituals remains reasonably constant, but the content varies quite a lot according to the inclinations and tastes of individual covens. Only initiations remain fairly standard, in order to ensure that they will be recognised across the whole Craft, should a covener wish to transfer to another coven.

Wicca is practised in a sacred circle, and most rituals have a structure broadly based upon the Western Mystery Tradition. This involves consecrating the space, orienting it to sacred geometry, raising some power, performing the ritual, sharing consecrated food and drink, and then closing the circle and bidding farewell to the beings and powers that have been called upon. Coveners usually bring a contribution to the feast.

The basic structure of a ritual is similar to that of a story. It has a beginning (the opening of the circle), a middle (the purpose for which the ritual is being conducted be it celebratory or magical), and an end (the closing of the circle).

There are eight festivals in the Wiccan year: Samhain or Hallowe’en (31st October); Yule (21st December); Imbolc (2nd February); Spring Equinox (21st March); Beltane (1st May); Midsummer or Litha (21st June); Lammas or Lughnasadh (1st August); and Autumn Equinox (21st September). The dates, practice and meaning of these vary according to where the coven is located, when particular plants actually come out, and the local traditions where the coven members live.

Most Wiccans practice magic for healing and other ethical results. The intention behind the working of magic is not to impose one’s will on the universe, but to bend the currents of possibility somewhat to bring about a desired outcome.

The Wiccan attitude to ethics is mainly based on the Wiccan Rede, “An it harm none, do what thou wilt”. I think this was originally meant to show that it is impossible to do anything without causing some harm, so it is necessary to consider carefully the consequences of one’s actions. To my mind, the most important aspect of Wiccan ethics is the list of the eight virtues which occurs in The Charge of the Goddess. These are beauty and strength, power and compassion, mirth and reverence, honour and humility. Each of these pairs of virtues points to the need for balance.

Most Wiccans believe in reincarnation, with the possibility of rest between lives in a region generally referred to as the Summerlands. Some believe that the spirit joins the Ancestors, whilst the soul is reincarnated.

My experience of Wicca

When I was about six, I had a series of visions, or maybe dreams, I am not sure, where I met with a god. It wasn’t clear to me at the time who he was, but I now think that he was Odin. He inhabited a rocky and hilly landscape which was fairly arid.

Later, I read the Narnia books, and all the Pagan elements – Talking Trees, Talking Animals, dryads, river gods, fauns – really stood out for me. I think I first tried talking to trees when I was twelve.

But the book that really made me realise that I’m a Pagan was Puck of Pook’s Hill by Rudyard Kipling. It turns out that Gerald Gardner, the founder of Wicca, was also influenced by this book, as he included one of the poems from it in his Wiccan ritual for Beltane, the festival of spring, merriment, and love.

I decided that I am a Pagan some time in 1985. I was pondering my values – of celebrating life and pleasure and the Earth – and realised that Paganism was a good label for my value system.

I first discovered Wicca in my final year at university. I had read Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex, and Politics, by Starhawk, and liked its message that darkness represents the rejected feminine side of life, and that darkness and light are equally sacred. I had always found the idea of the witch attractive – the idea of a healer, a shaman, and a woman who stood in her own power.

So, when I was introduced to a real Wiccan, and eventually got initiated into Wicca after I moved to Cambridge in 1991, I felt a sense of homecoming.

When I heard the words of The Charge of the Goddess for the first time, I found them overwhelmingly beautiful and resonant.

And whilst I have had moments over the years when I have disagreed with aspects of Wicca: especially the simplistic theology of a God and a Goddess embraced by some Wiccans, and the need for secrecy, and the way that some Wiccans are insufficiently inclusive towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people… I have always come back to that beauty, that sense of connection and homecoming, the feeling that I have found my tribe. A tribe of people who are individual and interesting, independent thinkers and wonderfully creative, who celebrate sexuality and wildness and the sheer joy of being alive.

I am also a polytheist, because I believe that divinity is manifested in many forms, and that the idea of an all-pervading single deity doesn’t stack up alongside the fact of the infinite universe. If the pantheist’s deity is the mind of the universe, it must be either so huge that it can’t be aware of our tiny consciousness, or it can’t be conscious in the same way that we are. So it would be difficult (as far as I can see) to have a personal relationship with it. With polytheism, I can have a personal relationship with a huge number of different deities, with different perspectives on life. There’s Mercury and Athena for intellectuals, Cernunnos and Artemis for those who like forests, Odin and Bragi and Brighid for poets and bards, and so on. Pretty much everyone has difficulty relating to the idea of the ultimate divine source, or to an infinite being – so people need to relate to something smaller.

In ritual, we express our deepest yearnings towards what we hold to be of greatest worth. In Wicca, it’s possible for a polytheist and an atheist and a duotheist and an animist to circle together, if we share the same values and a similar practice. Our theology is fuzzy, and there is a greater focus on experience than on theology. There is plenty of room for mystery in Wicca. We don’t know what the nature of the gods is, so all our theorising is probably inadequate, and most Wiccans acknowledge that. We are aware that we don’t know everything about the gods, and that we only see the faces they choose to show us; that sometimes it may be more illuminating to say what the gods are not than to attempt to say what they are.

In a Wiccan ritual, the words, the energies, and the space are beautiful and resonant. We have crossed a threshold into a new realm, a realm that feels closer to the gods and goddesses. This is the place between the worlds, where we walk on the edge of time and space, with one foot in the otherworld. The circle is a space where you can commune with the universe, develop the self, engage in sacred play, and honour the divine with each other. There is freedom from unnecessary social constraint. We celebrate the beauty of the night and the human body, and the firelight flickering on the naked flesh. The ecstatic leaping across the fire, wild and free. The flames, symbolic of life and passion… The feeling of journeying together to other worlds, communing with the ancestors, the land, and the spirits of the land. Walking with gods and goddesses.

I have now been practising Wicca for twenty-five years. After that amount of time, the cycle of seasonal festivals becomes part of how you see the world, and everything is seen in a Pagan perspective – looking for the most life-enhancing option in any given situation, seeing everything as a spectrum rather than as two poles of a binary choice, trying to ensure balance, create harmony, and care for the Earth and all beings upon it.

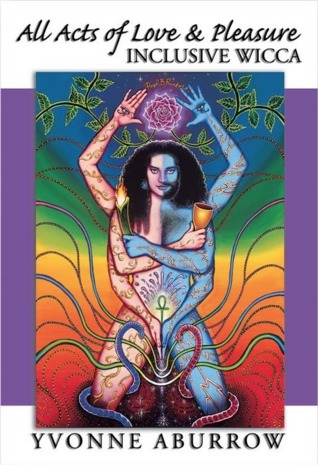

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.