I have been thinking for a while that the aims of Pagan traditions with regard to the self, soul, spirit, consciousness and its relationship with the Universe are different from that of other religions.

The cultivation of virtue

One of the aims in several Pagan traditions is the cultivation of virtue. In Heathenry, there are the Nine Noble Virtues; in Wicca, there are the Eight Wiccan Virtues; many adherents of Religio Romana try to cultivate the virtues which the Romans of antiquity valued. The cultivation of virtue assumes that the virtues will grow in fertile soil – the soul in which they grow is not choked by weeds, although a certain amount of weeding might be required to help the virtues to grow.

In Christian mysticism, by contrast, in order for the divine image to grow in the soul, there must first be kenosis – a process of self-emptying. One is then filled with divinity (divinisation in Western Christianity; theosis in Eastern Orthodoxy), and one’s divine image is restored (previously it had been bleared by sin).

In Wicca, there are three levels of initiation, and each involves an encounter with a different aspect of divinity – but there is no self-emptying. There is a stage where everything changes and is called into question, but that is the nature of such a journey, and is found in most traditions.

The kinds of virtue that are being cultivated are also slightly different. Whilst compassion is a virtue, it is wise compassion rather than indiscriminating compassion (this distinction is very important in Buddhism, where I first came across the idea). Other Pagan virtues include strength, mirth, honour (three of the Wiccan virtues) and courage, honour, self-reliance (three of the Heathen virtues).

Seeking the authentic self

Sarah Pike, in her anthropological investigations of Pagan festivals (documented in Earthly Bodies, Magical Selves: Contemporary Pagans and the Search for Community), found that the goal of the Pagan quest is to find the “authentic self” or the “true self”. This suggests that we are uncovering a pre-existing treasure, rather than erasing what exists and starting again.

The authentic self may turn out not to be “nice”. The Romantic poets were true individuals who produced great poetry; but they were not necessarily nice people (thanks to my friend CA for this example).

Most Pagans view the divine and/or deities as immanent in the world (or as immediate). Therefore the world is not fallen, and a multiplicity of forces – creation and destruction, yin and yang, growth and decay, energy and entropy, are in dynamic balance within it. These forces are also at play in microcosm in the human psyche, and that is entirely natural. Being angry, or sad, and acting on those emotions (in a controlled way), is not wrong – activism comes from anger, creativity can come from sadness.

The shadow and the psyche

A person with their shadow well-integrated can use its energy to provide them with power and decisiveness. A person with a well-integrated shadow knows how to say no, how to offer constructive criticism, how to avoid foolish compassion, and how to accept, welcome, and use the “dark side” of their personality (including anger, assertiveness, power, etc). They are also more interesting to know.

A person with no shadow (or no conscious access to their shadow) appears to be all sweetness and light on the surface, and presents as either generous, receptive, or passive, but when they eventually lash out, they do so from an ungrounded place, and are unable to connect their anger with the emotions that would balance it. Often, such people are “touchy-feely” and not analytical.

I have met a lot of “spiritual” people who are just too nice, and it seems false; they even talk in a high-pitched voice that sounds fake. There’s a great Monty Python cartoon where there’s a ‘nice’ vicar type with a soapy smile, but his smile keeps unzipping and letting monsters out of his head, so he has to keep nailing the top of his head back on. In other words, the more someone suppresses their “dark” side (shadow) and fails to integrate it, the more likely it is to lead to an explosion and an eruption of the shadow aspects (“monsters from the Id”).

Jung said that the work of individuation is all about integrating the energy from the Shadow and being able to use it creatively and constructively. As we bring the obscure unconscious material into the light of consciousness, it is transformed.

The psyche and the world

In Pagan communities, people do not attempt to shape others into any particular mould – there is no template for how the authentic self should look, because it is unique to each person.

Heelas and Woodhead, in The spiritual revolution (2006), talk about religions of humanity, that attempt to mould their adherents to a particular way of being and a set pattern of virtues. Most Pagan traditions refrain from doing this, and instead encourage individuality and a quest for the true self.

The relationship of the individual with the Pagan community tends to be more network-based. We meet in pubs for Pagan moots and gatherings, and the actual spiritual work happens in small groups such as covens, groves, hearths. People come together for large festivals, but there the quest is for freedom to be one’s true self.

Spirit and matter

In many spiritual traditions, especially those descended from Gnosticism, the aim is to leave the body and return to the divine source. (The radical rejection of matter may have been one of the reasons why orthodox Christians persecuted the Gnostics, apparently.)

In Pagan traditions, I would argue, because we love the land, or the Earth, or Nature (depending on the tradition), the aim is to awaken the soul of Nature, and to commune with the spirits of place (land wights, genii loci, and so on); therefore we want to bring more spirit into matter, not to separate the two.

Some people interpret “spirituality” to mean “the things of the spirit world”. Personally, I have always interpreted it as “a response of awe, wonder, and gratitude for the beauty of Nature, art, literature, scientific insight, and poetry” but increasingly it is being used as a term that means something to do with the non-material. It has also been described, by L Bregman, as “a glowing and useful term in search of a meaning”.

So I am starting to prefer the word “embodiment”, which is all about being in touch with your body, and not alienated from it. I am still (slowly) learning about embodiment practices. However, I think embodiment is probably a more Pagan concept than spirituality.

Conclusion

Given that Pagan traditions generally seek to cultivate the authentic self, and to put us in touch with the physical world, the wider community of other-than-human people (animals, plants, and spirits of place), and given that Pagans generally regard the divine and/or deities as immanent in Nature, we should be wary of importing spiritual practices, norms, and goals from other traditions without first checking how they fit with our existing goals, norms, and practices.

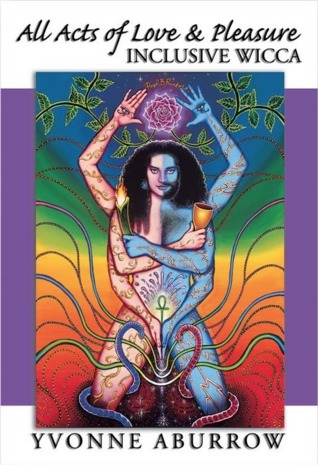

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.