There are different kinds of power, as famously identified by Starhawk (and probably others before her): power-over, power-from-within, and power-with-others. Authority comes in at least two flavours: being an authority on a topic (that’s why writers of books are called authors) and having authority over others. All of these are conferred by others to a greater or lesser extent (even power-from-within occurs when the pressure from inside is greater than or equal to the pressure from outside).

John Beckett writes that some people have a problem with authority. This is true, but sometimes it’s for very good reasons. We all mistake authority-on-a-topic for authority-over-others. Many bloggers have the experience of getting the comment “You can’t tell me what to do” when the authorial tone of their post was intended to be authority-on-a-topic and not telling others what to do. This is frustrating (but sometimes people get the authorial tone of their posts wrong, including me). But there are those who quite blatantly want to have power and authority over others, and use their powers of manipulation and persuasion and their apparent deep knowledge of a topic to gain power over others. They use the confusion over what is legitimate power and authority to create a mini-kingdom for themselves. These are the people and power-structures we should be resisting.

As Rhyd Wildermuth writes in a recent post, Gods & Authority:

Enclosure can happen for meaning, too. In fact, that’s always been the trick of Authority; convince people they have no other access to meaning except through their prescribed doctrines, just as Capital convinces us we have no access to exchange except through property and the market or the State convinces us we’ll die without it.

This is a situation that we want to avoid at all costs in the Pagan, polytheist, Heathen, Druid, and Wiccan communities. As soon as one person or group claims sole access to meaning, then they have enclosed meaning, and are in pursuit of power and authority over others.

The Buddha made a very sensible disclaimer about his teachings – that if they make sense to you, follow them, and if they don’t make sense to you, don’t follow them. Maybe we should all add that as a disclaimer at the end of our posts.

If someone says a thing that makes sense to you, then you would be well-advised to follow it. If it doesn’t make sense to you, don’t follow it – but do think about why it doesn’t make sense to you. Is it because you have an issue that is getting in the way, or is it because you have genuine solid objections to it?

Power and authority in groups

I have observed a number of different religious groups with different ways of dealing with power.

The Quakers make their structure as flat as possible, with elders and various committees. Sometimes the elders have too much power, but this is presumably balanced by the committees, and by the strong Quaker discernment processes. They also strongly recommend that people attend their classes on being a Quaker – so presumably those would also teach you about how to complain if somebody “forcefully eldered” you. I think we can learn a lot from how the Quakers do things. They also have regional Yearly Meetings in which all the Quaker meetings come together to discuss things, again using Quaker process. The disadvantage of this system is that the power is not out in the open where people can see it.

In Wicca, there is no formal power structure beyond the immediate coven. Covens have autonomy, and this is an important principle to most Wiccans. (Some groups have high priestesses who are referred to as Lord and Lady – but this is a North American innovation and is not done in Wicca in Britain, where we have quite enough aristocracy already, thank you. As far as I can tell, in most groups it is an honorary title only.) The system of coven autonomy has its pros and cons – it means that there can be very dodgy behaviour in a coven, and they can get away with it – but it does prevent hierarchy forming above and beyond that.

OBOD Druid groves generally have leaders, but different people are encouraged to lead rituals. They also have sub-groups for the different grades (bard, ovate, druid) and these could develop some odd power dynamics, but I haven’t observed any groups beyond the bardic grade, so I couldn’t say for sure. There is also the rather odd idea of the chosen chief of the order (who chose him? I didn’t vote for him…) but this seems largely ceremonial, as far as I can tell. (Please correct me if I am wrong.)

In Unitarianism, they have ministers and committees. In fact they have a lot of committees for such a small group. They also have an annual General Assembly (similar to the Quaker Yearly Meetings). The power of the minister and the committee generally balance each other. (Sometimes one has too much power, sometimes the other.) Congregations have autonomy, and there are also the important principles of the freedom of the pulpit (the freedom to state your truth in the pulpit) and the freedom of the pew (the freedom to believe your truth and disagree with what is said from the pulpit).

Authority (use of power legitimated by the structure) in the Quakers, Unitarians, and OBOD is fairly well-distributed in a system of checks and balances between the national body and the local regions and congregations. Wicca doesn’t have a national body, but we do get together to discuss things and we have a shared body of practices, as well as freedom to be creative. None of these systems are perfect, but they’re pretty good. There’s always someone with a big ego trying to gain power, but most of the time they are balanced by the structures that exist to regulate power and authority.

Freedom of belief, freedom of conscience

All of the above groups have freedom of belief: you can be an atheist, a pantheist, a duotheist, a monotheist, a polytheist, and so on. In practice there are not that many polytheists in the Unitarians and Quakers in Britain, but there are some, and both groups include atheists. What is important in all these groups is your values, including a willingness to play nicely with others. They do share a worldview, an ethos. As Caelesti writes in this excellent blogpost, Belief vs. Worldview:

Lived Values Follow Worldview – hopefully after developing a worldview, or during the process of developing one, values and ethics come to be a lived part of one’s life. This has been primarily what I have been focusing on this past year with my Self-Care Virtues project – the virtues are based on Celtic and Norse polytheistic worldviews, and there are also influences from my UU values.

It is also worth noting that these groups are mostly stable. Of course there are arguments about what it means to be a Unitarian or a Quaker or a Wiccan (and probably a Druid too, but I don’t know) but as every group has a variety of different preferences within it, I expect these arguments will never be definitely settled by a schism. Instead, there are affinity groups of Unitarian Pagans, Unitarian Christians, Quaker Pagans, Christian Quakers, and so on and so forth. And in terms of values, these groups generally have more agreement with each other than disagreement.

The emergent polytheist movement

I am largely observing the emergent polytheist movement from the outside and over the internet, so what follows is a somewhat partial perspective – but I have observed (and others have too) that there are some rather disturbing tendencies developing, which could in a couple of generations adversely affect the setup of polytheist communities.

Personally, I feel excluded by the polytheist movement. I have had too many polytheists tell me that I can’t be a proper polytheist because I’m a Wiccan (and it seems Jason Mankey has had the same experience). I feel excluded by all the people saying that there is only one way to be a proper polytheist, and that is to be a devotional polytheist. I feel excluded by the editorial policy of Polytheist.com, which is that they choose who they want on the site, and do not accept applications from prospective bloggers (contrast this with Gods & Radicals, whose editorial policy is basically “send in an article”, or Patheos Pagan, whose policy is also that people can apply to join, though that probably needs to be formally stated somewhere). I feel excluded by the increasingly narrow definition of what a polytheist is. Polytheism means ‘many gods’. That’s it. It doesn’t matter if you also believe that they are emanations of the divine source, or the underlying energy or whatever. That’s still polytheism.

This one of several reasons why I wrote my post on relational polytheism – the idea that we are in relationship with the gods, that we are co-creators with them of unfolding reality. It is possible to be a polytheist and a Wiccan – because I am one, and so are many others. My polytheism is different to Jason’s – but that is just fine.

If membership of polytheist groups and communities becomes based on a test of belief, then there will be persecutions of “bad polytheists” a few generations down the line. What matters is your values. Do you treat others with respect for their autonomy and freedom? Are you inclusive and welcoming of people with disabilities, LGBTQIA people, and people of colour? Do you care about the environment? Are you prepared to play nicely with other people who believe differently than you? Then you’re in my community. If not, take a hike.

As Rhyd Wildermuth says, how we world the gods says much more about us than it does about them. If we are authoritarian, the way we world the gods is as authoritarian figures. If we are egalitarian and peace-loving, we world them as egalitarian and peace-loving. He writes:

The gods exist as independent beings from us regardless of our belief in them. But it’s we who actually world them into the earth, and how we world them is dependent upon what we do, who we are, and the sort of world we create around us.

This is what’s going on with Heathens and Gaelic Reconstructionists who insist there must be a racial component to worship of gods. They are the sorts of people who believe in race, and therefore world their gods into the earth racially. The same can be said of people in those same traditions who insist there is no racial component; they don’t believe in race, and therefore don’t world the racism into the gods.

The true offering we give to the gods, which is precisely the same offering we give to any other living being, is this act of worlding. When I make offerings to Arianrhod, she’s not drinking that mead. Instead, by offering her mead or flowers, I am worlding her into the earth through the act of offering those things, but this is only a personal act.

So if someone claims that you don’t choose a god, a god chooses you, and that once the god has chosen you, you must do their bidding – then they are probably an authoritarian trying to world the gods as authoritarian. If they claim to be the chosen mouthpiece of the god, and try to tell you that they know better than you do who your personal deity is (or deities are), then they are trying to gain power over you. If someone claims that they are practising the One True Way for everyone, and you’re Doing It Wrong, then they are trying to gain power over you. The fact that there are many deities and many religious and spiritual paths suggests that there is no One True Way, in any case. If they tell you not to talk to certain people or types of people, that’s a power-grab. I wrote some warning signs of unethical groups for the Gardnerian Wicca website that are probably applicable more generally.

It is perhaps inevitable that some people will seek power and control. That means we have to create the structures, the checks and balances, that will prevent them from gaining too much power. As Syren Nagakyrie writes in this excellent post, A Conversation on Power and Authority in Polytheism:

At the top, that power turns it’s gaze to control. To determining religious experience, to deciding canon, and who is worthy of their religion and who is not. Again, look at the world religions. Look at the history. This is not conjecture or conspiracy. This what we see happen again and again and again.

We have an opportunity to do differently, to try. Yes it means hard conversations. It means it will take time. But if this is not the work, then what is? If this is not an act of devotion, of dedication, then what is? I am led to believe that this is why some particular powerful deities, and the Dead, are making Themselves so known right now.

Draw the circle wide

As Caelesti pointed out in her post, people’s beliefs shift and change over time. We live in a culture and a time where it’s hard to be a polytheist. Some days people are atheists with polytheist leanings, some days they are full-blown polytheists, some days they are agnostic. It’s okay to have doubts; they are a healthy part of spirituality and religion. If you didn’t have doubts, how would you test ideas to see if they really came from the gods, or were just the product of your ego? If you exclude everyone who is a bit agnostic, and don’t allow them room to practice, then you might be missing out on good people, and you won’t be giving them an opportunity to experience the presence of the gods (and how they interpret that experience should be up to them). As Elizabeth I said, “I would not make windows into men’s souls”.

Belief and faith originally meant trust, not assent to a creedal proposition – and I really hope that they will come to mean that again. I hope that polytheist communities will not have a creedal test of membership, but develop a common set of practices and values that will attract people who want to live those values and practice those values and world the gods in a way that will make the world a better place for everyone, not just a privileged few.

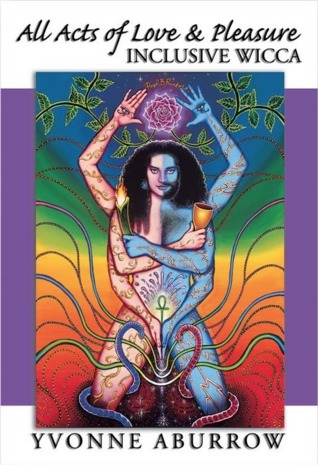

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.

thout darkness, we are left with the glare of brutal interrogation and too rigid certainty. There remains no mystery to seek. It is impossible to imagine a fluid dreaming without darkness. And what would we be without dreams? What would it mean if our shapes could never shift?

thout darkness, we are left with the glare of brutal interrogation and too rigid certainty. There remains no mystery to seek. It is impossible to imagine a fluid dreaming without darkness. And what would we be without dreams? What would it mean if our shapes could never shift?

![The Triumph of Civilisation by Jacques Réattau. [CC BY SA 3.0]](https://i0.wp.com/wp.production.patheos.com/blogs/sermonsfromthemound/files/2016/03/Gods-300x221.jpg)