Over recent years, there have been a number of controversies among Pagans which probably left a lot of newcomers to Paganism a bit baffled, especially when the terminology got a bit arcane. Sometimes different commentators on the issue also seemed to misunderstand and talk past each other on occasion.

I think these controversies are interesting and illuminating because they illustrate our concerns as a community, or as a network of communities, or a network of networks, or a patchwork of groups, or whatever metaphor you prefer to describe the contemporary Pagan movement.

So, in a spirit of inquiry and openness, not in a spirit of washing our dirty linen in public, and certainly not wanting to reignite these controversies, here is a summary of some of the most recent ones.

These controversies and discussions raise important questions of who we are, how we relate to each other as a community and individually, what we hold sacred, and how we relate to deities and the world around us.

The A to Z of Pagan controversies

I was not sure what order to present these in, as I think that ranking them by relative importance would be invidious, so I decided to list them in alphabetical order.

Atheist Pagans

Yes, there are Pagans who identify as atheists, and/or atheists who identify as Pagans. Humanistic Paganism is a large and growing community. Yet some people argue that the worship of deities is a key aspect of Paganism, and that therefore atheist Paganism is a contradiction in terms. However, there have been people who see deities as metaphors or archetypes for decades, and they have been welcome in Pagan rituals, especially in traditions that focus on practice rather than on belief.

The debate over whether Pagans can be atheists is important because it calls into question whether beliefs, practices, or values are at the core of religion, and which of them are more important for Pagans. It also relates to the idea that there are four centres of Paganism (Nature, Deities, the Self, and Community), and that different people and traditions will focus more on some than others. If you are not a deity-focused Pagan, then being an atheist and a Pagan works just fine.

Christo-Pagans

Pagans who also embrace Christianity in some form are pretty controversial because of Christianity’s historical persecution of Pagans, the claim of many Christian traditions to be the “one true way”, and their claim that its mythology is the only valid mythology. Several Pagan commentators have said that it is not possible to be a Christian and a Pagan, because of the exclusivist stance of Christianity and the extraordinary claims made about Jesus. However, there are so many variations within Christian belief about the nature and person of Jesus, that I can see how it is possible to be both Christian and Pagan in a variety of interesting ways. It would not be the path that I would choose to walk, but if people want to do it, then I wish them well (and I think it is rather exclusivist to claim that they can’t be Pagans).

Consent

Recently there have been several high-profile cases of Pagans abusing children, and incidents of sexual harassment at Pagan events. Many Pagans would like to think that such issues would not arise within Paganism, because we are so open about sex and sexuality. However, sex-positivity does not always equate with an acceptance that not everyone wants to have sex. There were many calls for Pagan events to have a safeguarding policy and a harassment policy. The issue also caused considerable self-examination by the Pagan community on what we should be doing about rape culture in our own communities and in wider society.

Pagans are very accepting of sex and nudity, but this enthusiasm is a problem when sex-positivity tips over into attitudes like ‘you’re a prude if you don’t want to have sex with me’. We need to have an ethical sex-positive culture.

Christine Hoff Kraemer and I are editing a collection of essays on Pagan consent culture, which we hope will become a valuable resource for people seeking to firmly establish consent culture in Pagan communities.

Apart from the very important issue of making Pagan communities and spaces safe for everyone, this issue has implications for how we view ourselves as a group, how we relate to each other individually and collectively, and how we cope with the fact of human fallibility.

Kinky Pagans

Z Budapest also caused controversy when she posted a comment that stated that she wanted to blow up Pantheacon because she saw a lot of kinky people walking around. Several people, myself included, found this remark to be deeply intolerant. I wrote a piece on why I believe that anti-kink attitudes have no place in Paganism.

There is a conversation to be had about the presentation of kink in a public space. Not everyone is comfortable with people wearing a collar and leash in a public space, for example (and that includes many kinksters who are uncomfortable with it). But the outright dismissal of the kink lifestyle is just plain ignorant.

This issue is important because, if Paganism is a sex-positive and tolerant community, we need to be tolerant of other people’s sexual preferences, provided that they are done by consenting adults. As the kinkster motto has it: “Your kink is not my kink, but that’s OK”.

Leaving Paganism

Thinking of leaving Paganism? Please close the door quietly on your way out. Lots of people have a crisis of faith, and leave Paganism either temporarily or permanently. However, there are good ways to do this, and bad ways to do it. A number of prominent Pagan bloggers have left Paganism, mostly to rejoin Christianity. Doubtless many of the things they were having issues with are real issues for the Pagan community to consider; some of the other things seem to be just a difference of perspective. Carl McColman is an example of someone who left Paganism gracefully, converted to Catholicism, but now works to build dialogue between Christians and Pagans, and promote mystical Christianity to other Christians.

It also behooves the Pagan community to react with grace and understanding to those leaving the Pagan community, and wish them well on their new path. Even if they are being a bit of a schmuck about it.

Some people reacted to these prominent changes of faith tradition with the notion that such people were never proper Pagans in the first place, and started to point the finger at other people who do not dismiss Christianity outright, or who embrace theological concepts that look superficially similar to Christianity. If anyone ever comes up with a definition of what a “proper” Pagan is, let me know – but so many hours have been spent on internet forums debating what Pagan actually means, that I very much doubt such a definition will ever be arrived at.

LGBT inclusion

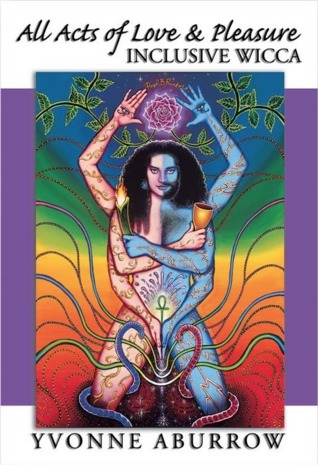

Paganism is not generally homophobic, but it can be heterocentric (centred almost exclusively on heterosexual symbolism). Many Pagans, especially some Wiccans, focus their devotion on a God and a Goddess, and often view them as a heterosexual couple, and insist on heterocentric interpretations of magical concepts like polarity and fertility. This can feel very excluding for LGBT people. Calls for a more inclusive version of Wicca, mine included, have caused considerable controversy in some quarters. I have explored the development of views of gender and sexuality in Paganism (part 1 and part 2) and so has Christine Hoff Kraemer. I also produced a video on gender and sexuality in Wicca, seeking to expand and deepen our understanding of the concepts of polarity and fertility, what tradition is and how it works, what we bring into circle and what we leave outside, and how to make Wicca more LGBTQI-inclusive, with examples from rituals and from history. I further developed these ideas in my book, All Acts of Love and Pleasure: inclusive Wicca.

Monism versus polytheism

Monism is the view that there is a single underlying energy in the universe. Polytheism is the view that there are many deities. Quite often, monists want to claim that the single underlying energy gave rise to the individual deities, or that it encompasses them, or that they are merely facets of it. This feels wrong to a lot of polytheists who feel that the deities are distinct beings, and that monism reduces unique experiences to a generic viewpoint. It is possible to reconcile the two viewpoints and have polytheistic monism (or monistic polytheism). There have been quite a number of blogposts from both a monistic perspective and a polytheist perspective. This matters because it is about how we relate to other Pagans with a different theological perspective, how we relate to Hinduism (which includes both monists and polytheists – if it can even be categorised using Western labels), and how we relate to our deities. Or perhaps monism and polytheism are just a matter of temperament?

The Pagan umbrella / big tent

Many people use the word Paganism, or the phrase ‘the Pagan movement’, as an umbrella term for all the various traditions that exist (Druidry, Feri, Heathenry, Religio Romana, Wicca, etc etc), but the Pagan umbrella is leaking, and some people are standing at the edge getting rained on.

People sometimes say that we are all taking different paths up the same mountain – but your mountain may not be the same as my mountain. One person’s Pagan path may be so different that they are not climbing a mountain at all – but their path is still recognisably Pagan. A lush and varied Pagan landscape seems like a better metaphor than a single mountain.

Still others say that an umbrella is too small, and what we really need is a Big Tent.

Jason Pitzl-Waters writes:

All of the recent debate over community, terminology, and theology, is, I think, a sign of our collective success. When our religions were under constant threat, when we truly feared jail, or worse, because of our beliefs, we huddled together for safety and solidarity. We created advocacy groups to speak for us, and empowered authors and activists to be our public face(s).

The more closely we try to define or describe Paganism, the easier it is to find someone who feels excluded by that definition or description, and ceases to identify as a Pagan. That is why models like the four centres of Paganism are really useful, because they give a conceptual framework for diversity of Pagan belief and practice. Many people feel that celebrating the diversity in the Pagan movement is important, and that we need to have a unified Pagan voice in order to communicate and negotiate with governments, other religions, and other world-views. I don’t think that unity and diversity are incompatible – but sometimes we need to emphasise our unity, and sometimes we need to emphasise our diversity.

Pagan veiling

Some Pagan women have experienced a call from their deities to cover their heads. As head-coverings for women are often associated with misogynistic attitudes and attempts to control women’s sexuality, the fact that some Pagan women chose to cover their heads was very controversial. Pagan women who chose to do this gave various reasons for doing so – because a deity had asked them to, because covering their head makes them feel protected, empowered, and blessed, as an outward sign that they are a priestess, as a sign of maturity, to increase confidence, and because it makes them feel sexy.

This issue is important and interesting for all sorts of reasons. Do you do something you might not feel like doing because a deity requests it of you? If you do something that means something very different in another culture, are you endorsing what it means in that other culture? Should we revive every practice that existed in the ancient pagan world? What is the meaning of covering your head?

Racism in the Pagan movement

To my mind, one of the most important issues in recent years has been the inclusion of people of colour in the Pagan movement, and how we relate to other indigenous religions.

Shortly after the protests in Ferguson over the killing of Mike Brown last year, Crystal Blanton asked for expressions of solidarity from Pagan individuals and organisations, which resulted in an outpouring of support. I feel that she should not have had to ask, but it was great that the support was forthcoming. One of the responses, from Covenant of the Goddess, was a bit vague and hand-wavy, and was strongly criticised by several bloggers. They have since revised their statement. Many of the writers on the Patheos Pagan channel responded to the call, and some were already writing about the topic. I collected together some of the responses from the Patheos Pagan channel on my own Black Lives Matter post.

Controversy erupted at Pantheacon 2015 when a satirical newsletter (PantyCon) appeared, sending up the tendency of white Pagans to fail to take notice of the experience of Pagans of colour, and specifically the original vague and woolly statement by Covenant of the Goddess. Several white Pagans thought that the workshop advertised in the satirical piece was a real workshop, and actually showed up for it. The satire was rather too close to the bone, and – together with several racist comments made by both attendees and presenters – made many Pagans of colour feel unsafe and unwelcome at Pantheacon. Jonathan Korman called publicly for an apology from the authors of the newsletter, and they did apologise. The founder, organiser, and sponsor of Pantheacon also issued a statement.

One of the positive outcomes of these events was a workshop called “Creating Brave Spaces for People of Color” which sought to begin a process of truth and reconciliation.

An excellent resource for understanding issues of racism and Paganism is the book, Bringing Race to the Table: Exploring Racism in the Pagan Community, edited by Taylor Ellwood, Brandy Williams, and Crystal Blanton. It has essays by a number of prominent Pagans, Black and white, and reflects on racism, the rise of the New Right, cultural appropriation, and related issues. I recommend it very highly.

Crystal Blanton is currently producing a great series of posts, the 30-day Real Black History Challenge, which is another great resource for understanding the reality of systemic racism, and how to start rooting it out.

Transphobia

The anti-transgender rhetoric emanating from certain Goddess-oriented traditions has caused considerable controversy. When CAYA coven organised a women’s ritual at Pantheacon 2011, where trans women were turned away at the door, Z Budapest defended this in very excluding and inflammatory language. Traditions which take an essentialist approach to gender tend to have difficulty coping with transgender people. There is an excellent post from 2011 by Star Foster explaining the issue. The British transgender activist, Roz Kaveney, even weighed in on the issue – and note that she appears to be under the impression that all Pagans are transphobic, which is not the case, but shows how damaging these kind of incidents can be. It is a shame that she did not do a bit more research, as a Google search on the subject will reveal dozens of blogposts protesting about the incident, and some defending it too. Neil Gaiman wrote about these issues in 1993 in a graphic novel, A Game of You, and the issues it raises are explored and explained by Lady Geek Girl. [1]

Wiccanate privilege

There was a discussion on Wiccanate privilege at Pantheacon 2014, but the debate had started in the Pagan blogosphere some time before that. John Halstead neatly summarises what “Wiccanate” means:

“Wiccanate” is a term coined by Johnny Rapture, and it refers to American Neo-Pagan theological ideas and liturgical forms common to large public Pagan gatherings and rituals, which are derived from Wicca, but are perceived to be “generic” or “universal” to Paganism. “Wiccan-Centric” is a related term. “Wiccanate privilege” is a phrase that has been going round in polytheist circles recently. It refers to the ways in which Wicca-inspired ritual and theology are assumed to be normative for Paganism as a whole.

The Wiccanate privilege controversy was a debate on how public and eclectic Pagan ritual is structured, how Paganism is represented to newcomers and outsiders, and how we define or describe Paganism. It was argued that, because most of the books and websites are about Wicca, and many public Pagan rituals are based on a vaguely Wiccan style of ritual, many outsiders and newcomers to Paganism think that Wicca is the only form of Paganism. Furthermore, the widespread assumption that everyone celebrates the eight festivals of the Wheel of the Year, or that everyone is a duotheist, or that everyone creates sacred space in a vaguely Wiccan manner (i.e. Wiccanate), means that other Pagan and polytheist traditions and ideas are marginalised within the Pagan community. I also feel that the widespread notion that Wicca is exclusively duotheist is harmful to Wiccans who embrace other theological viewpoints such as polytheism.

Where do these controversies start?

I am rather worried that this post makes it look as if nearly all Pagan controversies happen at Pantheacon. This is not actually the case, but because Pantheacon is a huge annual gathering, many controversies do get aired there. Controversies start in face to face interactions, get aired and discussed on the internet, and chewed over at conferences and pub moots and gatherings.

If you feel that I have missed out any controversies, or missed out any good links to articles on the ones described above, let me know in the comments. Links to good overview/introductory articles are especially welcome. I have mainly tried to focus on ones that might be especially baffling to newcomers and outsiders, and ones that have something to say about how we interact as a community, or as a linked group of communities.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.

This post is part of a series, Paganism for Beginners. All the posts in this series will appear in the category ‘A Beginner’s Guide‘. You can find them by clicking on the ‘FILED UNDER’ link at the foot of the blogpost.

[1] Thanks to P Sufenas Virius Lupus for pointing out that A Game of You was written way before the transphobia controversy, and hence does not directly address it, though it is relevant.