Some have argued that any form of theism is incompatible with science. Which is odd when so many scientists are theistic in some form or other.

Science and religion

The bitterest argument between science and theism is between evolutionary biology and creationist monotheism, for obvious reasons. According to my research [1], however, only about 50% of Pagans believe in a creator deity. Many would say that the universe was born, not made. And they would regard the Big Bang as the moment of birth.

Physicists, on the other hand, because of quantum theory, tend to be a bit more mystical.

It’s also worth mentioning that “compatible with science” can mean very different things to different people. Many rationalists tend to conflate rationalism and empiricism, but these are two very different world-views. Rationalism is the assumption that you can work out how the world works from a priori rational principles (such as “I think, therefore I am”). Empiricism denies the existence of any a priori principles, and states that we have to work out how the world works from experience. These two schools of thought were reconciled around 1900 in a new synthesis, but unless you’re referencing that synthesis, beware of conflating them.

There are also conflicts within science between a belief that science can work out and describe the nature of reality, and a belief that all our theories will only ever be a model of reality.

Pagans and science

The Pagan Revival has mostly had a pretty ambivalent attitude to belief. It started at a time when religion generally was on the back foot because of the advance of scientific understanding of reality. The response of religion generally has been either to say that religious accounts of creation are a metaphor (liberal religions like the UUs and the Quakers, and much of mainline Protestantism), or to retreat into fundamentalism.

The Pagan Revival mostly started from the assumption that the scientific account is correct, and proceeded to creatively work within it. Academic studies of Pagan beliefs suggest that most people have come to belief from significant disbelief and that they shift about on the belief spectrum.

Pagans don’t generally believe in a separate spiritual or supernatural realm; rather, we believe that spirits are immanent in Nature. I think that “spirits” and “magic” are properties of nature in the same way as consciousness is. Pagans revere the divine in Nature. 65% of my sample agreed that deities and other spirits have developed out of our social and ritual interaction with place and space, and 72% agreed that the divine is (or deities are) immanent in the universe. 20% were neutral on this issue. (The ones who didn’t agree that the divine was immanent in Nature were also the ones who didn’t believe in the divine.)

Instead, Pagans interact with the preternatural, as described by Michael York [2]:

The supernatural as we know it is largely a Christian-derived expression from the idea that its ‘God’ is over and ‘above’ nature – material/empirical reality. It is this notion that is the target of secular and naturalistic animosity alike. Instead, rather than ‘supernatural’, I turn instead to the ‘preternatural’ that expresses the non-causal otherness of nature – one that comprehends the magical, miraculous, numinous, mysterious yet non-empirical quality of the sublime. Most important, however, the preternatural does not demand belief or faith but instead encounter and experience – whether through contemplation, metaphor, spontaneous insight, ecstasy, trance, synchronicity or ritual or any combination of these. As Margot Adler expressed it, paganism is not about belief but what we do.

Luhrmann [3] identified four possible positions which magical practitioners take in justifying their views to skeptics. The first is realism, the idea that ‘there is a knowable objective reality and that magic reveals more of it than science’. The second position that she identifies is the two worlds view, that ‘the objective referent of magical claims is unknowable within the terms of an ordinary, scientific world’. The third position is relativism, which ‘defines all truth as relative and contingent’ (which Luhrmann found to be quite a common view). The final position is the metaphorical view, that magic is metaphorical and is probably objectively not true, but is nevertheless a creative and enjoyable practice.

It has also been suggested, by Jonathan Woolley [4] among others, that the US experience is very different from the UK, because there’s a much higher level of religious belief generally in the US. Hence why devotional polytheism has hardly gained any foothold in the UK. And Canada is different from both, though it is hard to generalize about it as yet).

Consciousness as emergent complexity

When discussing the existence of gods, it would be more accurate to talk about the nature of gods. At a minimum, gods exist as an idea. Anyone can grasp the idea of, say, Aphrodite. If you have a concept of something, it exists as a concept. But is Aphrodite a meme? an archetype in the collective unconscious? a cosmic process with a personality? an actual non-incarnate mind floating about? a physical being in another plane who can somehow manifest in this plane?

What we know from the science of consciousness is that the consciousness that inhabits our brains is an emergent property of the complex biology of our brains.

What I think is that therefore it’s possible that gods/spirits are emergent properties of the complexity of the universe. They are not supernatural, i.e. not separate / distinct from nature, but preternatural, emergent identities. Not necessarily persons or entities. Just as people shape each other’s personalities by social interaction, so we can shape the “personality” of a place by interaction with it. Hence the concept of the numinous, the genius loci.

Creative uncertainty, shared values

Taking rigid positions on theology is a fairly unproductive pursuit. People who insist that all theists are irrational believers in supernatural entities are creating a caricature of theistic beliefs that most theists would not recognize as describing their nuanced beliefs and hypotheses. People who insist that atheists cannot be Pagans are obviously wrong, as there were atheist pagans in antiquity, and there are atheist Pagans now, as Mark Green [5] points out.

We don’t know what the nature of gods is, but many people do experience the world as having consciousness. Others do not, and that’s fine. But many people exist in a sort of twilight zone between those two positions, and are quite happy in that space. Most would be very uncomfortable if forced to pick a side.

It’s my view, as a relational and mystical polytheist, that our relationship with the world around us (animals, birds, the ecosystem, and other human beings) is more important than our relationship with the gods. We can only ever guess what the gods want, if they can be said to want anything, so we should base our moral decisions on what we can see and know; on the fact of our embodied existence in an ecosystem that humanity is close to destroying.

The urgency of climate change, habitat destruction, and extinction compels those of us who care about the planet to work together, regardless of belief (or lack of it) in gods. If we have shared values, let’s work together.

References

[1] Yvonne Aburrow (2008), Do Pagans see their beliefs as compatible with science? MA Dissertation, Bath Spa University.

[2] Michael York (2009), A Pagan Defence of Theism, Theologies of Immanence Wiki.

[3] Tanya Luhrmann (1989/1991), Persuasions of the Witch’s Craft: Ritual Magic in Contemporary England. Harvard University Press.

[4] Jonathan Woolley (2015), The Matter Of The Gods, Gods and Radicals.

[5] Mark Green (2019), An introduction to AtheoPaganism, AtheoPagan blog.

Further reading

Yvonne Aburrow (2008), A Pagan response to Dawkins, Part 1. Stroppy Rabbit blog.

Yvonne Aburrow (2008), A Pagan response to Dawkins, Part 2. Stroppy Rabbit blog.

Yvonne Aburrow (2008), Transcendence. Dance of the Elements blog.

Ethan Doyle White (2015), An Interview with Yvonne Aburrow, Albion Calling blog.

Yvonne Aburrow (2016), Mystical Polytheism, Dowsing for Divinity blog.

Yvonne Aburrow (2018), The God-Shaped Hole, Dowsing for Divinity blog.

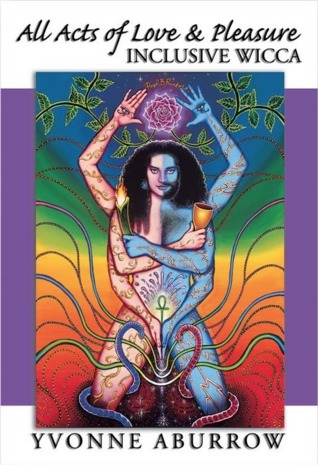

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.

Oh Yvonne, I can’t reply in just a blog comment! The short answer is that science and mysticism are compatible, limbs of the same tree if you will. The long answer gets into the collective consciousness, thought forms, animism, and even the bulk of particle physics.string theory. The conclusion is that anything we generate is but an imperfect model of something that our own brains/minds cannot fully comprehend, for a number of reasons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes this too!

Honestly I wrote a whole dissertation on this so I found it hard to address in one blog post!

LikeLike

“Our relationship with the world around us (animals, birds, the ecosystem, and other human beings) is more important than our relationship with the gods.” That pretty much sums up my position and it is how I define animism. These relationships are real, meaningful and terribly significant. I am a bit disturbed by the tone of some atheists. There is so much anger there, so little tolerance and nuance. Of course, not all atheists. haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! All of this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes–Atheopagans would say the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hence me saying that we have much in common, values-wise.

LikeLike

Consider me a devout agnostic! Nature, the world that we know exists, is far more important to me as a Pagan and simply as a human being than gods which we don’t know exist or not. If pressed, I’d say that gods are anthropomorphic personifications of powerful forces of nature languaged through human relationship, but that’s a long winded way of saying nothing much! If you believe in gods and that helps you live a good life, then I have no issues with that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have relationships with various gods, hence ‘relational polytheism’ — regarding the gods as allies rather than beings that we’re supposed to serve.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course it is. Anyone who thinks otherwise is stuck in a monotheist worldview.

LikeLiked by 1 person