Yule is a turning point in the year. In a way, this is true of every festival in the Pagan wheel of the year, but it is said that the word Yule means a turning point.

There are many facets of Yule. There is the anarchic element of mumming, Saturnalia, the bean king, boy bishops, the lord of misrule, the inversion of the usual order of things. This aspect seems to be inspired by the concept of turning, and of liminality: being on the threshold, being neither one thing nor the other.

I learned recently (from the excellent Fair Folk podcast) that the 12 days of Yuletide are intercalary days, making up the difference between the lunar year and the solar year. That certainly contributes to a feeling of liminality.

The most significant thing about Yule for our ancestors was probably that it is dark and cold outside, and the best response to that is to lurk indoors and make lots of nourishing food, light the candles, and snuggle up under blankets and furs. This response to the season still exists in the popular Danish concept of hygge, and the urge to deck your house with as many fairy lights as possible. We also know that this is the darkest it is going to get, and the days will start to get longer after the solstice. Axial tilt is the reason for the season, after all.

But that sense of liminality, otherness, and strangeness can also give rise to a more reflective mood. This is where old customs like Modranecht, or the Year Walk (another thing I learned about from the Fair Folk podcast on the 12 days of Yule), serve to create a space for going inward. On Modranecht we reflect on female ancestors, known as the Disir – a subtly different practice than focusing on ancestors in general. The Year Walk is a silent walk that is meant to foretell the year to come.

“The belief in prophetic signs bound to specific and important dates can be seen all over Europe as early as Medieval times, with weather and harvest divinations being the most common kinds (Cameron 2013:65-67). In Sweden, one oracular method was a ritual known as year walk, and those who ventured on this perilous journey were known as year walkers. Success meant that the omen-seeker could acquire knowledge of the following year; it was a ritual that sought answers regarding the unbearable uncertainty of being.”

– Tommy Kuusela, “He Met His Own Funeral Procession”: The Year Walk Ritual in Swedish Folk Tradition

Each festival on the year’s wheel is a chance to pause, and reflect, and take stock of what has been, and attempt to scry into what is to come. I do not believe in “living in the moment” – while it does not help to dwell overmuch in the past, or to worry excessively about what is to come, it is good to reflect, and take the omens, and enact rituals that connect us to the great sweeping currents of life and culture, that root us in the past so that we can put forth branches into the future.

In the past, life was much more uncertain: you were more likely to witness the death of a loved one from hunger, illness, violence, or childbirth. You yourself might die. So taking the omens at moments of liminality when the veil between the worlds is thin was a matter of survival, not just a quaint parlour game. The same was true of building strong connections with your community: a person who was outcast from the community lost most of the things that made life bearable and survivable.

Now, we mourn the draining of meaning from the cultural commons, the enclosure of meaning in walled gardens, and the loss of cultural memory caused by the commercialization of the holidays, and assimilation to bland, generic whiteness. But we can recover the many layers of meaning and beautiful customs that are available from the winter solstice, and weave their magic and wonder once more into our lives.

Previous writing about Yule

- Anarchic Yule (2022) – an exploration of the wilder elements of Yule

- Names for Pagan Festivals (2021) – You might be wondering where the names of contemporary Pagan festivals come from, and why some of them them are controversial. Here’s a brief history of where they come from, and why it matters.

- Pagan festivals (2020) – Pagan festivals (and traditional, Indigenous, Earth-based festivals around the world) are mostly about the cycles of the year.

- The Yule Tree (2019) – what does it symbolize, when do you put it up and take it down?

- An inclusive wheel of the year (2018) – ways of making the wheel of the year inclusive for everyone.

- Yuletide entertainments (2017) – some of the stories I like to revisit at this time of year.

- The Gift of Naughtiness (2015) – a short story for Yule, pushing back against that horrid species of busybody, the elf on the shelf.

- Paganism for Beginners: Festivals (2015) – setting Yule in the context of all the festivals of the Pagan wheel of the year.

- Yule (2013) – The sun rises at its furthest south, and rises in roughly the same place for three days, hence the name “solstice”, meaning “Sun stands still”. The Anglo-Saxons called the festival Yule; the Old Norse word was jól.

- A gift for a gift: a Pagan ethic of reciprocity (2012) – seeking to create a healthier culture of gift exchange.

This post is also available on my Substack. I plan for my Substack to have longer content, like essays and reflections and so on, but for now, I am posting everything here that I have posted there.

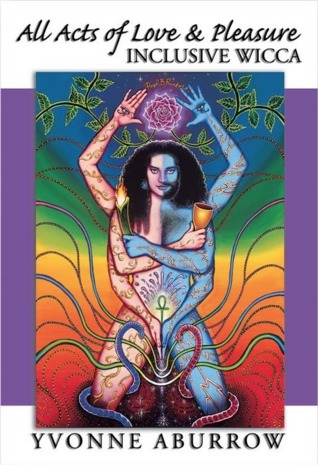

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.

Pingback: The Winter Solstice 2022 (Tonight at Midnight) – Adventures of A Mage In Miami